Well Protected

Sharp spines, thick shells, noxious odors — the lengths a tree will go to protect its seed! I found these while exploring a local cemetery in my new hometown.

Alive among the dead, the American chestnut really caught my attention. Once the predominant tree of Eastern forests, they are a rare find today. A fungus nearly killed off the entire species by 1940. In contrast, the ginkgo is an ancient survivor. Native to China, but planted widely in cities, ginkgoes have been on Earth since the days of the dinosaurs. I had never seen the nut before and, as it turns out, for good reason. The female, seed-bearing trees are not planted frequently because of the noxious odor given off when the nut drops to the ground and is crushed. Hickories are widespread in the mid-west and eastern U.S., so they are not hard to come by. The thick husk and hard nut protect an edible seed inside.

This page was done a piece at a time, starting with the chestnuts. I drew them directly in pen on location because the spines were so sharp I could not carry them home. I collected the ginkgo and hickory nuts and sketched them at home. Much of the watercolor was done with a very dry brush to get the detail. I added the text last with a micron 02 pen. (Stillman & Birn Zeta journal)

In Between

At Slocum’s River Reserve near Dartmouth, Mass, I found myself drawn to the quiet beauty of the salt marsh on an overcast day— all gold and green, tinged with red. In between land and sea. In between one place and another. There is a silent ebb and flow; life in flux each hour, each day, each season. My time here is a gift at the end of a hectic summer, made possible because I too am in between. This place, painting it, is my own calm between seasons, between moving out and moving in.

Watercolor in Stillman & Birn Zeta sketchbook

Organized Chaos

What a mess! This page, my life! Boxes and bins multiply through the house as we make our final push to pack for our move from New York to Connecticut. My desk, my art supplies: dismantled, boxed, and wrapped…for now. And so no lovely birds, no gardens, no carefully observed scenes until the chaos subsides.

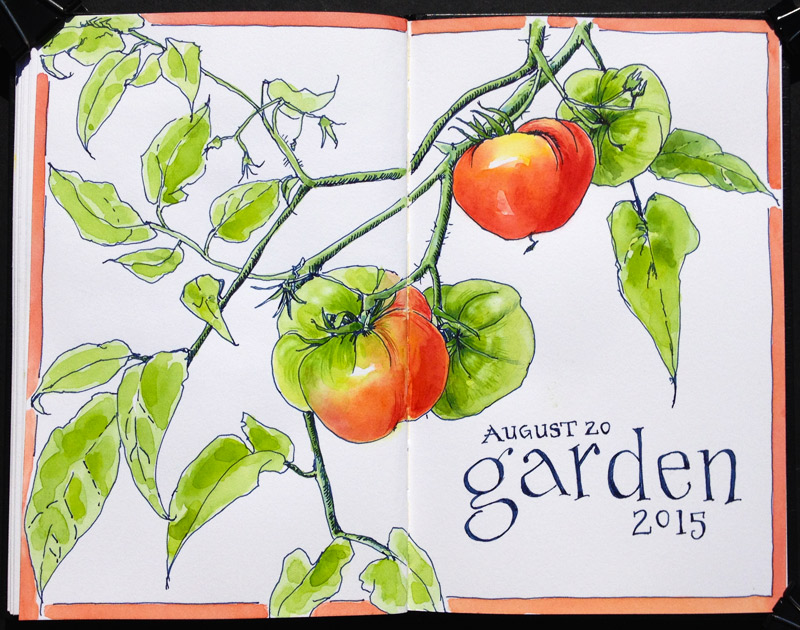

Home Grown

It’s very satisfying to grow your own tomatoes. Not just cherry or grape tomatoes, which are fine, but full-sized Brandywines or beefsteaks. While other gardeners have been harvesting their tomatoes for a few weeks, my late-maturing heirlooms are just beginning to ripen. And I suppose that’s good. The slow yield has given me one or two to eat and more on the vine to paint.

This page is a bit of an experiment. I recently bought a new fountain pen—a Lamy Safari—and I tested it with a deep blue-gray waterproof ink from De Atramentis called Fog Gray. The extra-fine pen nib is still much, much thicker than my go-to Micron 02 pen. Although I loved the smooth line, I’m not quite used to the bolder stroke. I found it hard to get much subtlety, especially when shading, which I tend to add in ink before beginning the watercolor. I look forward to more testing!

If at first…

Why is it that so many artists, including me, think we’re going to get it “right” the first time? I know that producing good art requires practice, trial and error, and problem solving. But I still get frustrated when things don’t turn out to my satisfaction.

Cohoes Falls- 1st attempt

So it was this week when I tried to paint Cohoes Falls in upstate New York. On my first go, I just didn’t get the drawing right. I found it hard to simplify the landscape into shapes that I could tackle. And I didn’t really figure out the values before trying to add color. The result: a piece that’s blobby and confusing.

So…turn the page and try, try again. Here’s my second attempt:

It was challenging to capture the magnitude of the falls and landscape in my small journal…to get the full width of the falls requires reducing the height. An accordion fold journal might work best. But that would take a third try!

About Cohoes Falls: New York’s second largest waterfall (behind Niagara Falls), Cohoes Falls is 1000 feet wide and 75-90 feet high. Several dams divert water from the falls, so the volume is of water over them is not full force, especially in summertime. Still, they are mighty impressive. There is a terrific park overlooking the falls and, when conditions permit, a stairway and trail that allows access at the base of the falls.

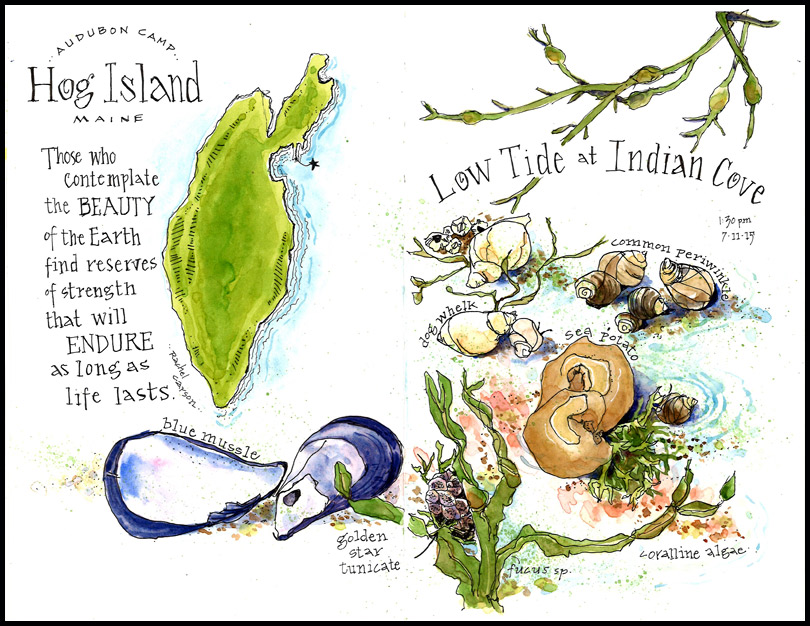

The Edge of the Sea

For many years now, I’ve clamored over granite ledges, slippery seaweeds, and sharp barnacle-laden rocks to explore the watery realm of Maine’s tide pools. When the sea retreats at low tide, a world of strange and tenacious creatures is revealed. I go in search of spiny urchins, orange and green sea stars, feathery anemone, scampering hermit crabs and slow moving snails, tunicates, blue muscles, dog whelks, sponges, lurking crabs and, always, the unexpected. I bring my sketchbook and a pen and draw until the tide turns.

After this year’s adventure, I went back through my sketchbooks over the last 10 years to compare the drawings and the treasures found. Enjoy!

Out of the Blue

Of the 123 million pounds of lobster caught on the Maine coast each year, only one in two million comes up blue. I was among the lucky few to see this genetic mutation, hauled up by lobstermen in Muscongus Bay.

The lobstermen were nice enough to hail our boatload of artists and photographers from Hog Island Audubon Camp and share their catch with us. They couldn’t have picked a more enthusiastic audience. All camera’s were immediately focused on the prize before the lobstermen released it back into its watery home.

FYI: Regardless of the color of lobster when caught, all turn red when cooked.

Arts and Birding

I’ve just returned from the rocky coast of Maine, where I had the privilege and pleasure of leading a weeklong workshop on Arts and Birding at the Hog Island Audubon Camp. Our group of 25 consisted of artists, photographers, and writers from all over the U.S. (plus one from the Netherlands), who share a passion for birds and the arts. There were many highlights—and I’ll share a few in subsequent posts—but here is one:

I’ve seen a good number of ospreys over the years, but never one so close. Hog Island instructor and osprey expert Dr. Rob Bierregaard and Chris Desorbo, a wildlife biologist at Maine’s Biodiversity Research Institute, banded this juvenile to the delight of camp participants. Ospreys are common on the Maine coast, thanks to the work of dedicated conservationists who brought them back from the brink of population collapse in the 1970s.

As countless cameras zoomed in, I decided to try my hand at sketching the scene. I had been encouraging participants to try quick ink sketches, so it was a perfect opportunity to practice what I preach. I went back in later with watercolor and painted only the osprey to highlight the star of the show. I did the first sketch (top) using a photo that I took after Rob and Chris finished banding the bird and its hood was off. I started with a pencil sketch, then outlined in ink, painted with watercolor, and finished the page with the text.

A bit more about banding birds

- Researchers outfit young osprey with lightweight aluminum bands on their legs. The bands contain identifying information which is later recovered. Banding studies reveal critical information about sources of avian mortality, where birds migrate, how they disperse, and how long they live.

- In 2000, researchers began tagging Ospreys with satellite transmitters that enable them to follow the bird’s movements around their nests and during their migration to South America and back. Learn more >

Five Days Later…

This page follows the one I posted on June 14, Things Worth Noting. A lot is going on in my life, which has made it hard to find time for art. I started this more than a week ago and I can hardly keep up– the daisies are now open; the iris unfurled; my son is leaving again. I need to paint faster!