The Lovely and the Lowly

I broke my home-bound suspension yesterday just to paint magnolias in bloom. I went to a nearby cemetery where I’d seen them previously. I was not disappointed; several large trees were in their full glory. Amidst the quiet of gravestones, their display was enjoyed only by birds and a few passersby.

Later at home, I inadvertently dug up an acorn just starting to sprout in my garden. Though lowly, it struck me that this unfolding life was as lovely as the magnolia. And, thankfully, right in my own backyard.

Later at home, I inadvertently dug up an acorn just starting to sprout in my garden. Though lowly, it struck me that this unfolding life was as lovely as the magnolia. And, thankfully, right in my own backyard.

International Nature Journaling Week is coming up, June 1-7. The week aims to bring together a world-wide community to celebrate and document the beauty and diversity of the natural world. As a lead up, artists and bloggers are sharing their perspectives and artwork each week at NatureJournalingWeek.com. I am grateful to be featured this week with a blog post “The Art of Discovery.”

At Home

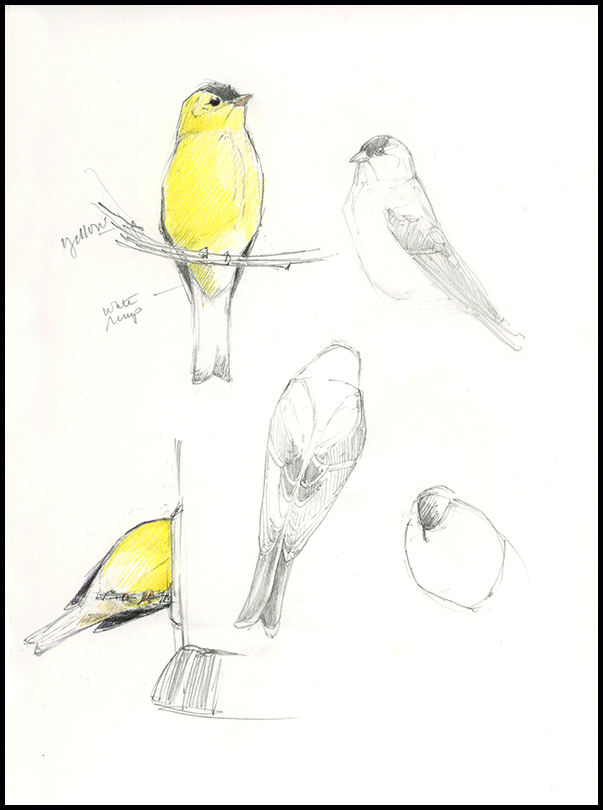

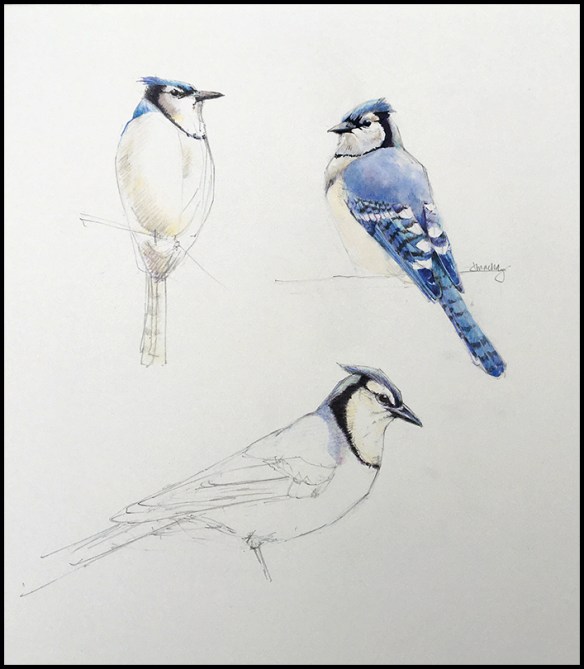

Being at home day after day (after day) is hard. I wear the gravity of our times like added weight. How grateful I am for our only visitors, who sing their way into spring with airy lightness. I leave my sketchbook by the window so I can draw birds at the feeder and take it with me on my post work rambles. So, today, I offer you a few birds from my yard in hopes that, for a brief moment, they might bring you the cheer that they have given me.

(Click to view larger: blue jays, goldfinches, bluebirds, palm warblers)

Tips and Techniques– For me, sketching birds from life feels a bit like entering a spinning jump rope. Even though the birds are moving, you have to jump in at some point and commit a pose to paper. Once I’ve done that, the bird has likely moved. So, I either wait until it strikes a similar pose or use binoculars to see markings in greater detail. Little by little, I add to the bird, paying particular attention to the beak and eye. I find that if you get those right, the rest of the bird, even if unfinished, is more convincing. Once the initial sketch is down, I use photos as reference for additional details. I sketched these with pencil (yes, I erased a lot) and colored pencil, with a bit of watercolor on the jays and bluebirds.

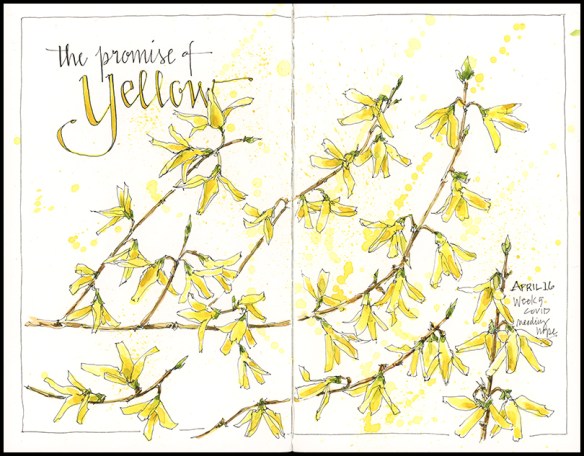

The Promise of Yellow

Sometimes, we just need yellow. Like when we’re waiting for spring greens to arrive after winter browns, or when the world has been turned upside down and we need a promise of hope. That’s when a burst of yellow forsythia or daffodils are just exactly right.

Click any image here to view larger. Tips and Techniques– I love the way petals of forsythia blossoms seem to dance. There is a movement to them that is really fun to draw. But to draw every bloom could be too much. You want the burst of yellow, without so much crowding that you lose the dance. In this case, a spatter of paint added a touch of loose, uncontrolled color that complemented the flowers without overwhelming them.

Tips and Techniques– I love the way petals of forsythia blossoms seem to dance. There is a movement to them that is really fun to draw. But to draw every bloom could be too much. You want the burst of yellow, without so much crowding that you lose the dance. In this case, a spatter of paint added a touch of loose, uncontrolled color that complemented the flowers without overwhelming them.

- A hard shake of a wet watercolor brush yields big drops (top left);

- A stiff craft brush or old toothbrush flicked with your thumb results in a tighter concentration of marks (bottom);

- An drop from an eye dropper about 10 inches above the paper gives big splashy drops.

If you don’t already use spatter in your painting, try it next time you want to enliven your subject or to achieve an effect that a controlled brush can’t.

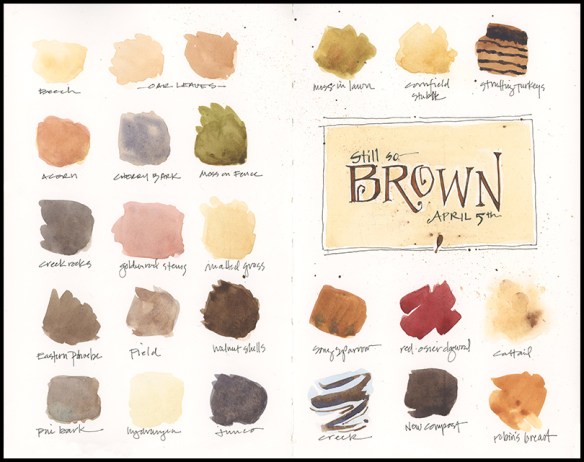

Color Play: Brown

You would think that this time of year would be about green. But it’s not. It’s still so very brown here in upstate New York. Sure, we’ve had a few green shoots and buds, but the palette is overwhelmingly somber. I couldn’t bring myself to focus on any particular subject today, so I went outside and embraced brown in all its muted, worn-out, post-winter shades. The result is as much a useful lesson in nature’s variety as it is in color mixing.

Tips and Techniques– You can make a wonderful variety of browns with just a few colors in your paint palette. My go-to favorites for dark browns and smoky grays are burnt sienna with ultramarine blue and burnt umber with ultramarine. I also like the subtlety of burnt sienna and cobalt blue. You can get some lovely warm browns with burnt sienna or burnt umber with alizarin crimson or quin gold. I also have both raw sienna and yellow ochre in my paint box. Although they seem very similar, yellow ochre leans yellow, while raw sienna leans brown, resulting in shades of green or gray when mixed with blues. If like me you are waiting for green, try some color play of your own.

Walk with the Dreamers

Walk with the dreamers, the believers, the courageous, the cheerful… This sentiment appealed to me long before the need to stay positive in the face of a global pandemic. But it’s worth rereading and reminding myself, nonetheless, and I hope you find it sound advice too. Usually I don’t have time for illuminated letters and lavish decoration in my journal, but a rainy Sunday seemed like the perfect time to work on something highly detailed.

Tips and Techniques– There are so many beautiful illuminated manuscripts that you can use as reference for elaborate borders and text. Try a quick Internet search for images (“illuminated manuscripts”) and you’ll be lost for hours looking at letters and borders and wondering how anyone ever created such masterpieces by candlelight. I sketched this border in pencil and painted it in gouache. The gold is ink, painted on the page. I wrote the first sentence of text with a stub-nib Pilot Metropolitan fountain pen and the rest with a regular nib. You could use a dip pen, if you prefer. My favorite books for calligraphy:

The Art of Calligraphy, A practical guide to the skills and techniques by David Harris

The Bible of Illuminated Letters by Margaret Morgan

The Speedball Textbook (I have the 22nd edition, but current edition is very similar)

Spring Arrivals

Early spring is underrated. The splashy colors of daffodils and tulips are still weeks away, as is the return of more prized migratory birds– warblers, tanagers, orioles. The woods, too, show only the slightest hint of green. And yet, despite temperatures that fluctuate between 20 and 55-degrees, between snow and sunshine, spring unfolds in myriad small ways each day. I keep a list of spring arrivals, marking the date and the species. I like to compare my lists from year to year, to anticipate what’s coming next, and to celebrate each small sign of the changing season. It’s not only the resplendent that deserves our applause.

Tips and Techniques– People often comment here about my page layouts, so I thought I’d use this page to try to shed some light on my process.

Picture yourself, faced with a blank page. Then someone hands you a most splendid scarlet mushroom, unearthed from rotting leaves near the wood pile. It goes on the page. You’ve never seen this mushroom before, so you look it up in a field guide and record information about it. Now the page is begun, but what next?

Several days later, while walking down the road, a flock of grackles sits perched on last year’s stubs of corn in the field. It’s the dried stalks as much as the birds that draw you in. They go on the page. Now you have two seemingly unrelated subjects to contend with. Hmmm.

The next day, it snows, bringing flocks of birds to the feeder. There’s no time to draw them, but you make a list. Two days later, its 50-degrees with wind from the south, a fairly good sign that there will be birds that take advantage of the tailwind and come north. They go on the list. Now the page seems to be saying something about early spring, but it needs something more to pull it together. Red maple! Blooming now, it’s just the thing to carry the color of the scarlet cup across the page, so you go in search of it and add a few blooms.

Finally, you add a title “Early Spring Arrivals” to solidify the theme. But there is still room for one more thing: you need to put yourself on the page. Why did you see these things? Because you are teleworking from home and taking more walks while COVID-19 transforms the world. That seems worth noting. And now the page is complete.

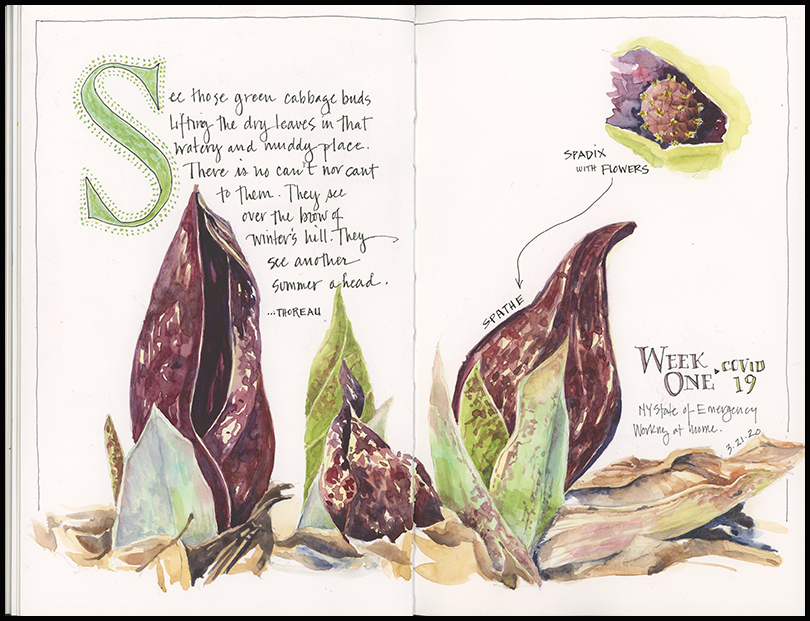

Prophet of Hope

Yesterday was overcast and damp, but I went searching for signs of spring along the wooded streamside anyway. “If you are afflicted with melancholy at this season, go to the swamp and see the brave spears of skunk-cabbage buds already advanced toward a new year.” Leave it to Thoreau. His timeless wisdom relevant still. And as much of the world shuts down to stem the spread of coronavirus and my state braces for the worst to come, I need that swamp, that skunk cabbage, Thoreau’s insight more than ever. “See those green cabbage buds lifting the dry leaves in that watery and muddy place. There is no can’t nor cant to them. They see over the brow of winter’s hill. They see another summer ahead.”

Tips and Techniques– Which came first, skunk cabbage or Thoreau? I typically go out and sketch what I find outside and then follow up with research. I look up some natural history information about what I’ve drawn, and sometimes look for a relevant quote or poem. I’ve been thinking all week about the role of art in times of struggle, and about how to record and express some of what I’m feeling. Finding Thoreau’s quote, written in 1857, could not have been more fitting.

A most egg-cellent collection

As a follow up to my most recent posts on painting bird eggs from the collection of Frederic Church’s family, I thought you might like this egg-cellent post from NYS Parks & Historic Sites’s blog about how the collection is being cleaned and prepared for exhibition. You’ll get a glimpse of the eggs, learn more about their history, and get a sense of how exciting it is to see them in person. Work on the eggs continues in the state’s conservation lab (which has very limited staff in an isolated environment), but the exhibition, slated for May 9 – November 1, may be subject to delay. View the post>

Small Works of Art

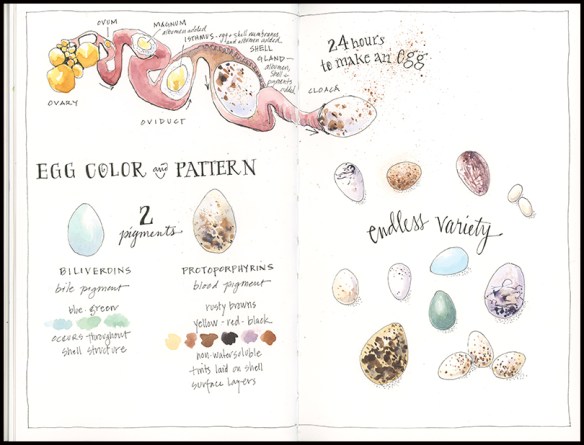

Last week’s post An Extraordinary Collection generated a number of questions about bird eggs. I thought I’d answer them with another egg page and a bit of background.

How eggs are made: It all begins with a female reproductive cell called an ovum. As it travels through the bird’s oviduct, layers of albumen (the egg “white”) and shell membranes are added. When the egg reaches the shell gland, more albumen is added, along with a calcium rich shell. The hard outer shell takes about 20 hours to complete and the whole process takes a day. The egg is then expelled from the bird’s body, and Voila! there it is.

- It is illegal to collect bird eggs, so working from museum collections or photos are your best options. Looks for Victorian-era collections in natural history museums. I’ve also seen them in libraries and historical societies.

- Practice getting the curve of the egg with just one or two lines. You may want to rotate your paper to help you make the curve. The cleaner the edge, the better.

- Some eggs are glossy, and others dull; regardless, leave a highlighted area on the egg to help give it dimension.

- Work like a bird. Build up color on the egg in several layers. Start with the “ground” or base color. Then add darker tones and shadows, followed by surface markings.

- Build up surface colors and patterns in layers, working from light to dark. A rigger brush is excellent for scrolls, while a spatter brush is most effective for creating random spots.

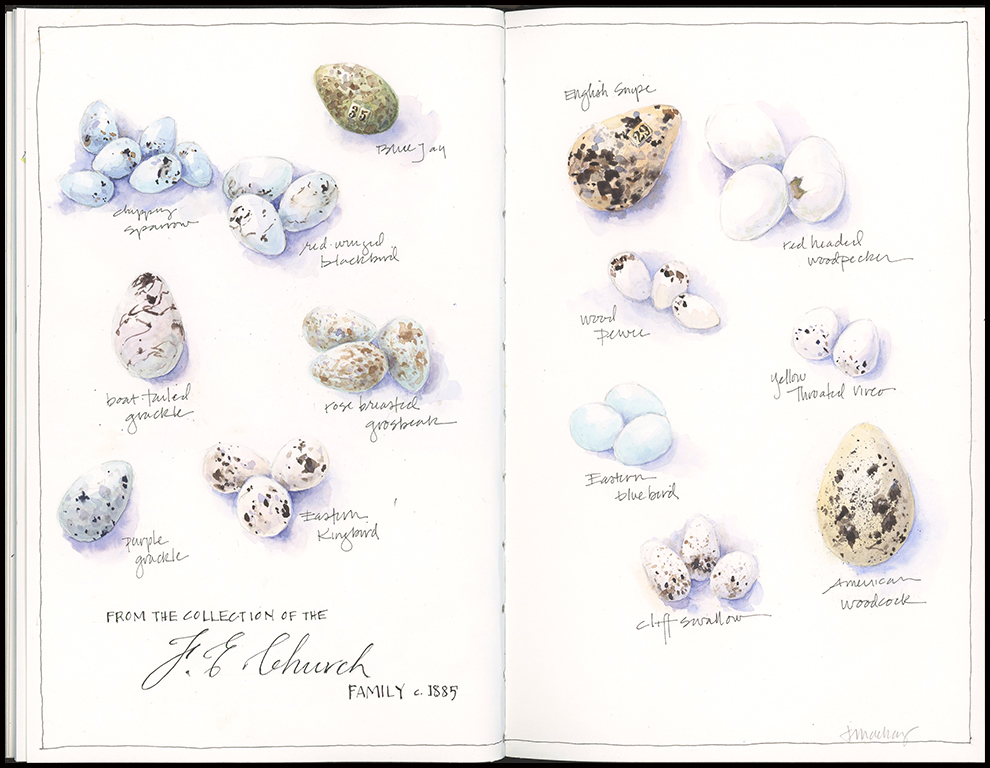

An Extraordinary Collection

I have had an incredible opportunity this week to draw and paint bird eggs that are more than 135 years old. Even more remarkable is that the eggs were collected by the children of American landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church. Until recently, the collection of more than 200 different types of bird eggs has been sitting in a large wooden chest in the attic at Olana, Church’s home overlooking the Hudson River. The eggs were brought out to be re-cataloged and prepared for an on-site exhibit at the Olana State Historic Site near Hudson, New York.

I was invited to take an early look at the collection and quickly noted that many eggs had been mislabeled when they were last cataloged back in the 1960s. Some bird names were misspelled, others were incorrect, and, in a few cases, the bird name has been changed by ornithologists. My work with birds enabled me to provide some useful resources to the conservator, who will work with a small team of experts to prepare the exhibit. Once that happens, the eggs that are displayed will be protected under glass and the rest will return to their crate. In the meantime, I hope to have a few more chances to paint more of this extraordinary collection.

Tips and Techniques- The huge range of colors and markings on bird eggs come from just two pigments. These are combined at different intensities and in different ways as translucent layers of eggshell are created inside the bird. Watercolor makes a perfect medium for replicating this process, as multiple transparent layers can be laid down to create an egg. Egg colors are very subtle and quite variable, so I like to keep a scrap sheet handy to test colors before putting them on an egg. This practice works well for any painting, enabling you to get the right shade and amount of water on the brush before painting with it. Your test sheets may occasionally make nice bookmarks, too.