Unshelved

Most museums have far more of their collections tucked away behind the scenes than on display. Used primarily for research—or often just sitting in temperature-controlled storage—the public rarely gets a look. But as luck would have it, my visit to California coincided with an exhibition called Unshelved at the San Diego Natural History Museum (The Nat). On display were birds, mammals, and insect specimens in display cases that harkened to museum displays of yesteryears, before museums decided to shelve specimen cabinets in favor of exhibits that placed species in greater context of the environments in which they are found. Unshelved suited my old-school natural history sensibilities perfectly. I tucked into a corner with seldom viewed bird nests and hummingbirds and couldn’t have been happier.

Tips and Techniques- When sketching in a museum be prepared for two givens: using limited materials and peering eyes. Most places will allow sketching in pen or pencil, but not paint. Sketch out the main things that interest you and take a few photos to work from later. Expect visitors to be curious about what you’re doing. Some will simply peek and move on, while others will comment. I especially love it when kids take interest. I use the opportunity to ask whether they like to draw or to tell me about their favorite things in the collection. If you can let go of feeling self-conscious, those moments will become a precious part of your experience.

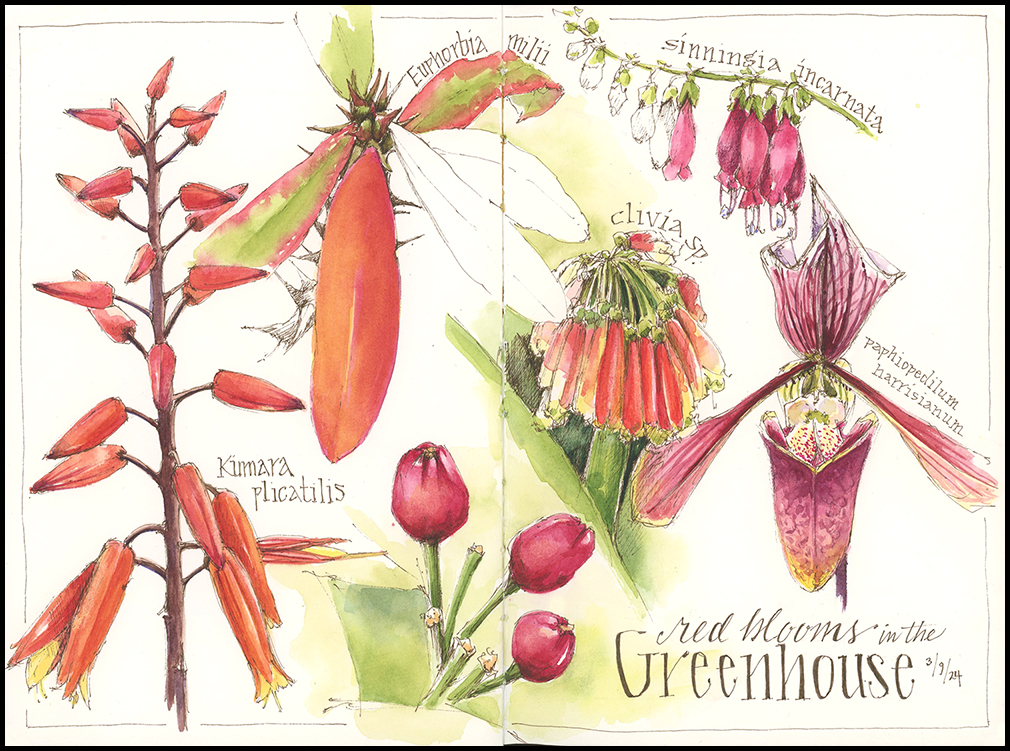

Red Blooms in the Greenhouse

I met three artistic friends last weekend for a few hours of sketching and good cheer at the Lyman Conservatory at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts. It’s always a treat to be surrounded by greenery during the transition from winter to mud season. As it turned out, hundreds of other people felt the same way. The place was packed. I had to be careful in the cactus room not to back into spines when letting people pass me in the aisles. And when I thought I had found a good spot to tuck in amidst the tropical plants, an acapella group arrived to serenade visitors. The music was lovely, but crowds soon followed. I wouldn’t trade my visit, or the chance to enjoy red blooms in the greenhouse, but I’ll appreciate the solitude of painting along the roads and fields once again.

Tips and Techniques– Focusing on a single color is a great way to explore different hues and even test pigments that you may not use much. Mix your primary color with hints of other primaries as well as secondaries to push the dominant color in different directions. For example, mix reds with yellow, blue, green, or brown to see what variations you get. The goal is to get to know your paints, and figure out which ones mix well together and which you like best.

If you’d like to take a deeper dive into color, join me for Painting the Colors of Spring, starting March 28.

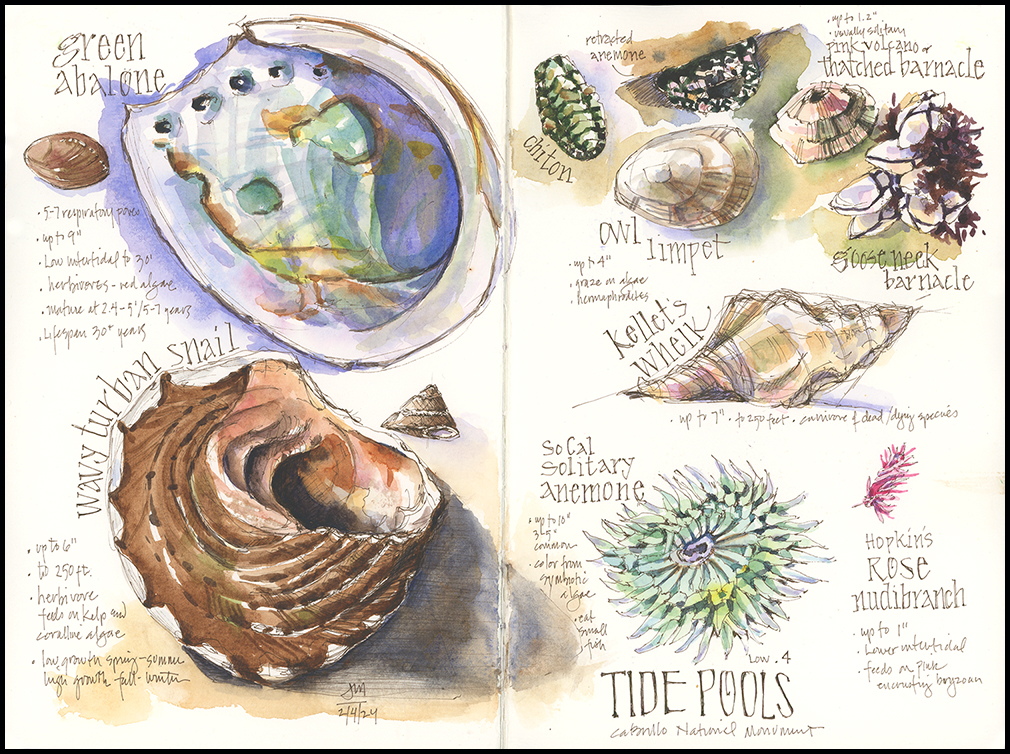

King Tide

While visiting southern California last month we took time to explore the tide pools at Cabrillo National Monument. This is one of the best protected rocky intertidal areas in California and our timing was perfect. Sun, moon, and Earth aligned during our visit to create a King Tide, a twice-yearly occurrence in which the low tide is nearly two feet lower than normal. This exposes far more of the rocky shore and reveals a greater diversity of the fascinating creatures that live at the edge of the sea.

Tips and Techniques– I love sketching while exploring tide pools and encourage you to try it if you have the chance. Though conditions are challenging, the sense of discovery and immediacy is exciting—and those qualities often come through on the page. The rocks are slippery, the water frigid. Creatures are hiding to try to stay damp and safe until the tide returns. And if you explore the outermost pools where sea and land meet, you need to watch the waves and the time to be sure your route back isn’t covered in water from the incoming tide. I carry my sketchbook and a pen in a plastic bag in my backpack, along with a small ruler, and a bandana for drying my hands. I accept that my sketches will be messy—that comes with the territory—and I add text and watercolor later from photos and memory.

It’s Complicated

Consider the brittle star – a simple marine creature comprised of a central disk with five arms extending outward to gather bits of food. Now multiply each arm by two, and two again, and again, and again…and you have a magnificent basket star. I saw this one, Gorgoncephalus eucnemis, on my recent visit to Scripps Institution of Oceanography’s Benthic Invertebrate Collection in La Jolla, California, and I was entranced. These creatures live in deeper ocean waters so, unless I take up scuba diving, I will never see one alive. I think it might be the most complicated thing I’ve ever drawn.

Tips and Techniques- When faced with a complicated subject, break it down into manageable pieces and take your time. I worked on this for more than a week, an hour or two at a time. My prior work painting tangled bird nests and tree branches certainly helped. But this was larger and more complex. Were I to do it again– and I might— I would paint each section in turn, rather than using ink to help define the spaces. Here’s a look at my progress from start to finish (sorry the photo quality isn’t better, the lighting wasn’t great).

Check it out! Botanical Art & Nature Sketching Retreat with Wendy Hollender, Lara Call Gastinger, Giacomina Ferrillo, & Jean Mackay, Friday, November 8 – Sunday, November 10, 2024, Ashokan Center, Olivebridge, NY

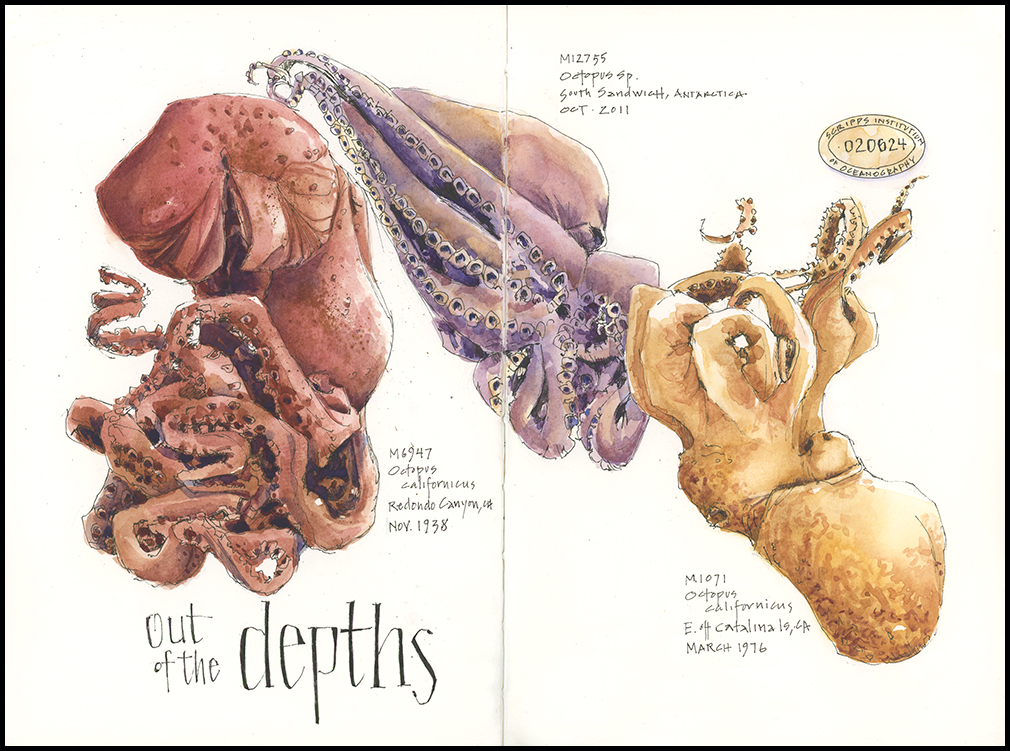

Out of the Depths

Row after row, jar after jar: 55,000 containers representing 800,000 specimens and 7,600 species from the world’s oceans lay in front of me. Like a kid in a candy store, I had to choose. Giant crabs, exquisite sea stars, ghostly squid, mollusk shells of all sizes and stripes—these creatures without a backbone make up the Benthic Invertebrate Collection at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. On a recent trip to Southern California, I arranged to spend a few hours sketching there, and what an amazing opportunity it was. After roaming several rows of otherworldly organisms, I decided to focus on octopuses. Admittedly, there is something slightly grotesque about dead sea creatures preserved in jars of alcohol, but that is countered by the their continued magnificence, the wonder of studying them firsthand, and the challenge of giving them a new life on paper.

New class: Registration is open for Painting the Colors of Spring beginning March 28, online at Winslow Art Center.

A Collection of Feeder Birds

If you feed birds in the winter, you know that watching what comes and goes can brighten your day and connect you with what’s happening outside from the comfort of your windows. We have a great variety of birds year-round and I like to keep a record of what shows up each season. Among my favorites is a pair of red-bellied woodpeckers whose heads glow flaming red when the sun shines. I was glad to give this bird the spotlight on this illustrated list and let him steal the show in my sketchbook and outside.

Note: February 16-19 is the Great Backyard Bird Count, a citizen science project where people from around the world submit records of the birds they see over the course of a few days. It’s managed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the National Audubon Society, and Birds Canada and participation is free and easy. Find out more: https://www.birdcount.org/

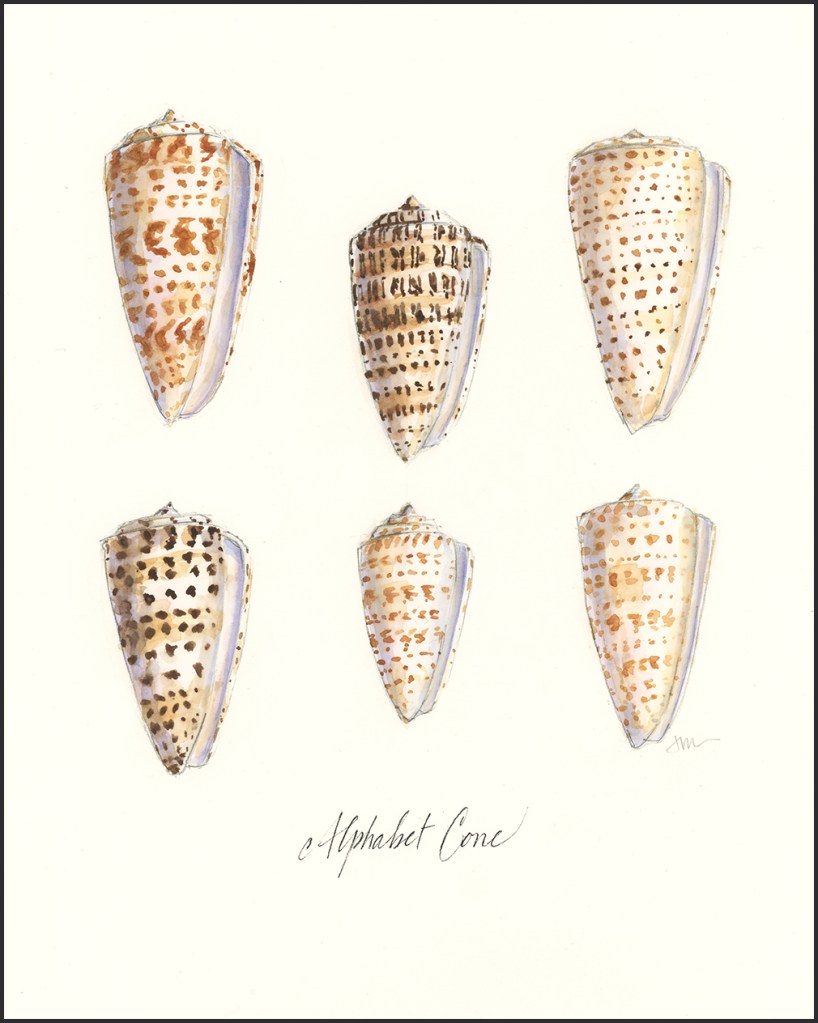

Anatomy of a Shell

How many of us have picked up shells on beaches, turning over a smooth and perfect whorl, or marveling at the pearly shine inside a clam or mussel? We owe our fascination, of course, to the mollusks that created and lived out their lives in these structures, and then left them behind for the sea to recycle or someone to find. I hadn’t really thought much about the anatomy of shells before, but it’s time I learned. This page illustrates some of the major features of both bivalve and gastropod shells, along with a few different types of shells. The second piece reflects my fascination with Alphabet Cones. I’m headed to the California coast soon and this will give me a whole new understanding when I am exploring tide pools, strolling the beach, and painting my finds.

Tips and Techniques- If you’ve stowed away a few shells from your beach wanderings, pull them out and take a closer look. Sketch them from a variety of perspectives. Notice how the body whorl spins around the central axis and how each whorl grows substantially larger with each rotation. Don’t worry about copying every line and detail. Work on getting the shape first. The colors are often so subtle that it’s worth starting quite light and paying attention to the values so that you can make the shell dimensional before going too dark.

From Bulb to Bloom

I’ve enjoyed watching my amaryllis over the last month as it shot up out of the bulb, grew taller each week, and finally exploded in colorful blooms. I drew it each week and ran out of room on this page just as the blossoms emerged. When I tried painting the flowers on a new page, I found I couldn’t do them justice in the confines of my sketchbook. So, I started again, this time on a 12×16 sheet of hot press watercolor paper, and that did the trick.

Tips and Techniques- Look for subjects that lend themselves to a series. Like the amaryllis, it could be plants emerging and blooming. Or try the opposite and sketch flowers as they pass peak and wilt. You could also choose fruit to draw from different angles or an apple or pear as you eat it. It’s a good exercise to compose a page of several like objects and fun to watch and record as something grows or is diminished.

Simply Complicated

It was a banner year for the White Pine tree in our yard. Laden with green cones at the uppermost branches throughout the summer, the tree rained down pinecones throughout the fall. I decided to collect a basketful before winter, thinking I might find them useful as holiday décor. They did, indeed, look nice in an old metal basket on our back porch, but the more I looked at them, the more I wanted to draw them. The simplicity of this sketch belies how very challenging that was to do. My plan was to paint five or six cones of varying sizes, but after the first, I changed my mind. And here you have it.

Tips and Techniques– If you want a drawing challenge, pick up a pinecone. There is a fractal design underlying their spiral structure and, while knowing that helps, it is still easy to get lost trying to figure it out. I recommend starting with pencil and using the darker values to help you find your way.

Brushstrokes

How do we measure a year? In months, weeks, days, hours? Or perhaps in moments lived. Experiences remembered. In births and deaths. In friends made or lives touched. Miles walked. Milestones achieved. Breakfasts and dinners shared. Gardens planted and harvested. Travels taken. Birds come and gone. In what we create, give, leave behind. In brushstrokes, bold and subtle. I hope you’ve made some good marks in 2023.

Thank you for following and sharing your thoughts and feedback. I’m very grateful for your support.

Tips and Techniques– When drawing outside in winter, try to capture as much information as you can before stopping. Block in major shapes, note values, and add a few details if you can. Then snap a photo and add more details and color indoors to finish. I sketched this nest directly with a Micron 005 sepia pen while standing in a thicket of goldenrod and new white pines as the late afternoon light faded. I’m not sure what bird made this nest, but it certainly chose a tangled spot. It was a struggle to unravel both nest and vines before my feet got too cold and sent me packing. Still, sketching outside opens good possibilities for winter subjects, and I’m always glad to be outdoors poking around.